27 July 2011

I’m not being facetious. We think of paper as a timeless commodity. We’ve all heard the story that the word was derived from the Greek name of a plant called Cyperus papyrus, and if you are like me, you probably figured that was what they made paper out of in ancient times. After all, we have ancient Egyptian, Hebrew, and Greek writings that date back close to two millennia BCE. Paper must have been one of the earliest inventions of mankind.

It ain’t necessarily so. Papyros was used as a substrate for writing in ancient times, but its relationship to paper is really in name only. The substrate was made of woven strands of the the plant fiber and was probably almost as hard to make as to write on. More common for the writings of the Bible, the ancient Greek philosophers and playwrights, and government lackeys was animal skins. We commonly refer to the scraped and treated hides of animals used for writing as vellum or parchment. This substrate was so commonly used that even at the time of Gutenberg, 45 of the copies of his famous Bible were printed on vellum. That’s 5,000 or so calfskins!

Paper as we know it wasn’t really invented until about the 2nd century BCE in China. It made its way slowly westward by way of the Islamic world to Europe in the 13th century CE. The paper-making process had advantages over using animal skin as nearly any fibrous plant could be used to make the paper. The plant was ground and mashed up with water, then shaken out into sheets and dried. At our home, we went through a long period when my daughter was about 8-9 where slurry was made in the blender out of various types of scrap paper, was shaken out on a hand screen, and then plastered against a window to dry. She used the homemade paper to make holiday cards, books, and school demonstrations.

Some of the contemporary terms we use to describe paper come from the process. For example, “laid” refers to the imprint of the drying screen on one side of the paper (the side on which it was laid). “Deckle” refers to the raw, uneven edge of the finished sheet, now neatly trimmed off the paper we put through our inkjet printers. And “watermark” is the subtle logo of the paper manufacturer that was a part of the drying screen and left a faint trace on the paper that you can usually only see on fine papers by holding them up to the light. Even the term “ream” is derived from the Arabic word rizmah that translates as “a bundle.”

One of the key elements in the thriller The Gutenberg Rubric is how manuscript and book dating is done. Determining the location of the manufacture of the paper can lead a long ways toward identifying the time and place of the printing. The carbon breakdown in organic matter is traceable and can lead to relatively accurate dating of a substrate.

For more information about the history of paper, Neather Batsell Fuller, Instructor of Anthropology at St. Louis Community College, has written an excellent paper that can be found at A Brief History Of Paper.

(The Gutenberg Rubric, a novel by Nathan Everett, will be released on July 28. Order your copy today!)

22 July 2011

What was it about books that really changed when we entered the digital age? At first, it was little more than the input. In 1986, I was publishing a variety of association journals and newsletters. I was driving from typesetter to printer with a bunch of keylines when I saw a billboard that advertised a Desktop Publishing Seminar. That day I bought my first computer (Apple 512k Fat Mac) and publishing software. I waited three months for Aldus PageMaker to be released so I could really start publishing electronically. But the process I used post-computer was for publishing was substantially the same. I simply did my design work and layout on the computer and produced the keylines whole instead of doing paste-up. Later, I went direct to negative without keylines, and eventually even experimented with on-press imaging. The result was little more than the automation of a process that publishers had been using since the mid-50s.

The change came when shifted the delivery system. Instead of delivering content on paper, we began delivering content on-screen. According to the traditional designers and publishers of the day, we were out to kill the book. I have to confess, even though it wasn’t our intent, as a part of the on-screen revolution we did our part to maim if not kill.

First off, we destroyed typography. When the Internet was devised, it was a means of making text instantly available across a wide network. The text had no formatting. It was a wonder if we could even tell where paragraphs ended. But engineers had an answer. The World Wide Web came into existence and html provided the tools for formatting content. Having worked with computer programmers for the past decade and a half, it is no surprise to me that the “design” of Web pages more closely resembled computer code than books. The type choices had to be what was universally available and the proprietary fonts of the publishing industry were left out of the mix. Even when designers and typographers entered the mix, the results of their efforts remained buried in select software that did not transfer from device to device.

The resulting typography and, by extension, design was terrible, and it is no wonder that the bulk of traditional print designers eschewed the Web and then eBooks. Typography is terrible, letterspacing is terrible, there’s no pagination, the design falls apart, everything is linear, you can’t control what it looks like, it is unreadable. Sound familiar? Those traditional designers who did transfer into electronic design often attempted to assert their control by specifying type in number of pixels, forcing exact page sizes, and even embedding fonts or using graphic images of pages to preserve exact formatting. As soon as these pages left the computer they were designed on, they fell apart. Designers couldn’t control what readers read on.

Designing for eBooks is still a tricky process. Converting print documents (whether through scan or conversion of PDF or text files) often results in poorly structured content that cannot be effectively laid out on the electronic page. It takes a designer who understands the structural code of XHTML and CSS to create a good looking eBook, and one that understands the limitations of the various reading devices to create a great one.

Sometimes I envy the designers who worked with hot lead, but I imagine those who converted from hand-lettered manuscripts to the metal bits of type bemoaned the loss of artistry and control they had when they dipped a stylus in ink and drew each letterform on the page.

As shown in the story of The Gutenberg Rubric, there have been multiple revolutions in the design and creation of books. Each one requires the use of new tools and those who reach the highest levels of artistry do so because they take the time to learn how to use their tools well.

(The Gutenberg Rubric, a novel by Nathan Everett, will be released on July 28. Order your copy today!)

20 July 2011

Aside from adding power to the typesetting process and the printing press, very little changed about printing for 500 years after Gutenberg started the process. He could have walked into almost any print shop in the world in 1950, set type, and pulled a galley proof much the same way he did in 1450. In the late 1800s, two automated typesetting machines that cast the type bits in the same order that they were used in the text came into prevalent use, the Monotype machine and the Linotype machine. Interestingly, Gutenberg had already used the basic method (though not the mechanics) of the Linotype by setting the Catholicon in two-line slugs all the way back in 1460!

But in the mid-1900s, two developments changed the way printing was done as rapidly as the invention of the press—Offset Lithography and Photo Typesetting. Lithography had been around for quite a while and was a printing method based on the principle that oil and water don’t mix. Instead of resting on top of the bits of lead, the ink was held on a flat surface, collecting in the areas that were not moist. The ink was then transferred to the paper in a similar fashion to any printing press. But the offset process came about with the discovery that the ink could be transferred to a roller from the litho stone and then rolled onto the paper. This process was faster and cleaner than letterpress.

The development of photography had advanced significantly by the 1950s, and it was discovered that the photographic process could be used to create the lithographic plates. That meant that type could be set rapidly by simply photographing a page, or exposing the plate to a film negative of the type. By the mid-1960s, a revolution as fast as Gutenberg’s, the majority of printing was being done by offset lithography and cold type. The day’s of hot lead came to an abrupt end and by the mid-1980s it was almost impossible to find a letterpress in production use. Typesetters trained on the Linotype and Monotype machines were supplanted and a new era of printing was begun.

(The Gutenberg Rubric, a novel by Nathan Everett, will be released on July 28. Order your copy today!)

19 July 2011

In 1450, the process for creating books—whether in codex or scroll form—was to sit for several weeks with a pen and inkpot and copy a work letter-for-letter. By 1460, just 10 years later, the printing press had spread throughout Europe and was being used to mass-produce books. It all had to do with the invention of little pieces of metal type that each bore an individual character on it. Getting those bits of metal required several inventions, most of which we credit to Johannes Gutenberg.

First, there was the type design. The type used in the Gutenberg Bible was patterned after that found in a manuscript Bible of Mainz, which also served as the guide for setting the pages. While the Latin alphabet included only the basic 26 letters used today, Gutenberg’s design included as many as 250 different glyphs that spanned upper and lower case letters, punctuation, abbreviations, characters in various widths, and ligatures (double characters combined into a single glyph). For every character in the text, about 1/4 inch or 18 points in size, a punch had to be engraved. The punch was the perfect reverse of the letter form.

Then there was the matrix, or mold for the type itself. The punch was designed to make the impression in the mold into which the the hot lead was poured. The mold had to be reusable because many copies of each character were needed to keep the manufacturing process moving. If any letters were damaged in the process, they also had to be replaced.

Third, there is the alloy itself—one of the most remarkable parts of the invention. Movable type in clay and wood had been in use in China for some time, and there were already experiments in metal type in Korea at the time of Gutenberg. It seems unlikely that Gutenberg knew about these, but woodblock printing was certainly known in Western Europe by Gutenberg’s time. The problems with these various predecessors had to do first with the durability of the type to withstand repeated impressions under the pressure of the press, and the uniformity of the type. Even early printing examples from Gutenberg’s shop before the Bible show an unevenness in the height of the type causing a dark impression for some letters and a lighter impression for others.

In The Gutenberg Rubric, incunabulist Keith Drucker must master the art of casting the dimensionally stable alloy using only the measuring tools of Gutenberg’s day. The result of his work is crucial to unlocking the secret of Gutenberg’s code.

(The Gutenberg Rubric, a novel by Nathan Everett, will be released on July 28. Order your copy today!)

14 July 2011

Establishing a Distribution System

Books, in the Gutenberg world, are physical objects that must be in immediate proximity to the reader in order to be of use. Prior to the invention of the printing press, readers had to go to where the books were in order to read them. The books were in the libraries, usually of wealthy people or institutions (like monasteries and universities).

The books stayed put. The reader came to the book.

During the incunabula—the first fifty years of printing—the distribution system changed. Books were no longer stationary. By 1500, Aldus Manutius in Venice was producing octovo-sized books that could be “carried in a saddle-bag.” There are descriptions of book-sellers on the streets at every corner hawking their wares—the 16th century equivalent of Starbucks. This may have been the largest number of street vendors of books until the book-piracy wave in Peru began. As far as the distribution system goes, people still had to go to the book repository to buy them—often in uncut signatures that then had to be taken to a book-binder—but then they could take their books with them wherever they wanted to go.

Booksellers began to move off the street into storefronts. We had the birth of the bookstore.

But the distribution system is changing—in fact, has changed. Starting in the early 2000s, people began moving away from brick and mortar bookstores as they used the computer to order their books and have them delivered to them. Readers no longer have to go to the book at all. The book comes to them. As the book has gone through this change in distribution, it has also gone through a change in form. We no longer need the physical object to hold in our hands in order to read the book. The book can be delivered electronically.

Some pundits have declared that the physical book is an artifact of the distribution system. In fact, the distribution system was created to support the printing of books. Regardless, there is no question that the change in distribution over the past ten years is as radical as the change that occurred in the first 50 years of printing. It remains to be seen if brick and mortar bookstores will survive the change, if they will evolve into something new, or if they will simply fade away. What is clear though, is that the relevance of Gutenberg on the distribution system ten years ago was at a 10. Today…

Relevance of the Gutenberg distribution system: 5.

(The Gutenberg Rubric, a novel by Nathan Everett, will be released on July 28. Order your copy today and save 20%!)

13 July 2011

The Leveling of Content Value

Imagine a time when people gathered in public places—the church, temple, town square, palace courtyard—to hear the reading of words. The words they heard, be it scripture or decree, were important. They were so important, they had been written down so that every word could be repeated exactly to the listeners. These words had value.

Granted, storytellers and minstrels gathered crowds as well. They told tales and sang songs. They entertained. But there was no expectation that those stories were of utmost importance. After all, they had not been written down.

It was a costly endeavor to painstakingly copy a manuscript. It took months. It not only had to be accurate, it had to be legible and beautiful. At the time of Gutenberg, a full copy of the Bible cost about the same amount as a functioning vineyard.

Then came the printing press.

Of course, Gutenberg started with the Bible. His journeyman and successor then progressed to the Psalter. Gutenberg himself moved on to the Catholicon. Within 50 years (the term of the Incunabula or cradle of printing) Aldus Manutius was printing obscure romance (The Hypnerotmachia Polyphili) in a convenient octovo size (about the size of a trade paperback) that would conveniently fit in a saddle-bag for leisure reading.

Any written words were worthy of print. And no matter what the content, the books had the same value.

This leveling of content value has continued and advanced in the digital age. On a single page of Twitter posts, one might read an announcement by the President of the United States and what a 14-year-old had for breakfast. They are treated equally.

Some have decried the rise of self-publishing in this era as being the death knell of literature precisely because the reader can no longer tell what is valuable content and what is not. Indeed, the mainstream publishers would have us believe that we can only trust what they have published because it has been vetted, edited, and determined valuable enough to invest in. In reality, the vetting and investment have been based on what the publisher thinks will sell, not on the value of the content. We’ve all seen some incredible crap published that sells a lot of copies.

In The Gutenberg Rubric, the heroes strive to discover a cache of ancient manuscripts. The manuscripts could have immense scholarly and economic value. They would be the original words of some of the world’s great works. They could throw religious belief, national boundaries, philosophies, and even science into disarray, simply because they are of such value. How do we know they were of such value? Simply because they were set down before printing.

For good or ill, the relevance of Gutenberg in the leveling of content value: 10.

(The Gutenberg Rubric, a novel by Nathan Everett, will be released on July 28. Order your copy today!)

12 July 2011

The Stabilization (Stagnation?) of Truth

Gutenberg is given a lot of credit for making literacy a standard for all people. As Marshall McLuhan wrote: “Gutenberg made everyone a reader, Xerox makes everyone a publisher.”* After all, when only the wealthy could afford books and could hire scholars to read them, why would a common person need to read? But when books became a commodity and available to the masses, then being able to read made sense.

But how did people get information before literacy? Essentially, it was spoken from one person to another. Town criers came to the central square and called out news that had happened weeks or months ago. Preachers quoted the scripture from the pulpit. Decrees and laws were announced. And stories were told.

If you’ve ever played the game of “telephone,” you know what can happen to a message as it is passed from person to person. It can change—in fact, change is almost inevitable. Imagine an age in which all information is passed from person to person verbally. Even in highly disciplined scriptoria where scribes painstakingly copied manuscripts, it was possible to introduce and even to multiply errors.

As a result, doctrine, science, politics, and even history were in a constant state of flux. There was less importance placed on objective facts than on the mythology that surrounded them. It is, after all, the myth that is easiest to recall and repeat. Facts make a poor story. The myth reveals the truth that is hidden in facts.

Gutenberg changed that, for better or worse.

The advent of Wiki technology on the Internet has shown the possibility of returning to dynamic truth rather than stagnant truth. This has been greeted with cries that it can’t be depended upon. Yet we see more and more instances in which information presented through the editorial province of the community is depended upon more than objective proof from facts. Undeniably, however, the Gutenberg press changed, for good or ill, the way we view truth and facts.

Relevance score in the stabilization of truth: 10.

(The Gutenberg Rubric, a novel by Nathan Everett, will be released on July 28. Order your copy today!)

*I’ve looked all over for the source of this widely quoted statement and only find a reference to “The Weekly Guardian.” If anyone knows the actual source and date, I’d appreciate it!

11 July 2011

In the year 2000, Gutenberg’s invention of the printing press consistently ranked in the top ten (usually at number one) inventions of the second millennium. We love lists. Gutenberg’s invention was right up there with such notable things as the electric light, the telephone, the computer, space flight, and glass windows. But is the printing press, even in its current incarnations, still relevant as a history changing invention?

The Invention of Mass Production

We could argue about this for a long time, but I’ve chosen simply to start a few posts about what kind of contributions Gutenberg made with his invention of the printing press and how they permeate society today. Not surprisingly, very few of these items have to do with the physical invention itself. Yes, Gutenberg created a matrix punch system for creating molds. Yes, he got the formula for lead type dimensionally stable. Yes, he mixed an ink that would adhere to the lead and that could be transferred to a substrate and that would have blackness and durability to last centuries. Yes, he figured out how to adapt a wine press for printing. Isn’t that enough?

I find this amusing. Even with my eBooks and my e-reader, I find myself lovingly caressing paper books, beaming with pride over my newest release, feeling like “it is real” once I hold the physical object in my hands. Is there any other mass-production artifact that I feel the same way about? I’m not even that fond of my car. I disdain the coffee shops that use automated espresso machines to measure the coffee, tamp it to perfection, and force water at the exact right temperature through the grounds as “coin-op baristas.” I’ve always considered mass-produced and automated to be inferior to handmade.

Yet, for nearly five centuries after the Gutenberg Bible, the greatest technical advance in printing was adding steam or electric power to the press, removing it one step further from the craft of creating books. There’s nothing really like a good old-fashioned hand-written scroll.

But the impact of the printing press on the way we create things today is undeniable. Even the computers, smartphones, and e-readers we use to create and read electronic books are themselves manufactured and mass-produced. To be sure, we use robotics and sterile environments for the assembly-line work, but the process used is essentially the same one that Gutenberg used to automate the production of books.

Relevance score in manufacturing processes: 10.

(The Gutenberg Rubric, a novel by Nathan Everett, will be released on July 28. Order your copy today!)

21 June 2011

It’s summer Solstice, which makes it a perfect time to kick off your summer fantasy reading time. In my continued effort to join in the promotion of new books this year, I’ve chosen today’s release of Gary Caplan’s The Return of the Ancient Ones to really get my summer started right. And to celebrate Gary’s release, I’m giving away Steven George & The Dragon eBooks to everyone who buys a copy of Gary’s book!

Have you ever wondered what you’d get if you crossed an EPIC fantasy book with a twist of sci-fi?

Pure magic, right?

Gary Caplan's The Return of the Ancient Ones combines futuristic with fantastic! This Sword & Sorcery/ Fantasy hybrid will carry you into a well-crafted world reminiscent of Tolkien and J.K. Rowling.

No surprise this book is the winner of the "Fiction: Fantasy/Sci-Fi" category of the 2011 International Book Awards!!

Escape into a world of adventure and magic. And invite your kids along (ESPECIALLY any teenage boys you may know). Because, like the great otherworld epics before it, The Return of the Ancient Ones appeals to young AND adult readers.

The Return of the Ancient Ones illustrates how your fiercest enemy can become your most aggressive ally—a great reminder to never judge things by how they appear on the surface.

The hero, Gideon Finelen, holds an ancestral legacy that makes him the only one who can use the magical Sword of Order.

Dramatic, playful, and sublime, this book is what the fantasy genre was meant to be. If you want an escape from reality, this is a great read!

Once you order The Return of the Ancient Ones, you’ll receive an access code that will give you a free ePUB eBook of Steven George & The Dragon. Instructions are on the site when you follow the link below. You’ll find other great bonuses on the launch page as well. If you are buying for someone else, take advantage of getting a little gift for yourself as well!

This summer be swept away to another world. Escape the mundane around you and join Gideon and his friends as they fight to save their world in The Return of the Ancient Ones! Then drop into “once-upon-a-time” land to visit a dragonslayer who doesn’t know what a dragon looks like, where it lives, or how to slay it. It’s time to hit the hammock and get this summer started!

16 June 2011

I’m both elated and humbled after receiving this review of For Blood or Money on Amazon this week. I’ve no idea who the reviewer is, but I’ve become a fan of his! This is what “bobwriter” had to say:

Noir mystery meets the internet age

This quirky private detective yarn 'For Blood or Money' deftly combines the hard-boiled gumshoe prototypes like Sam Spade and Nero Wolfe with a cutting edge cyber-tech sleuth.

Dag Hamar is a detective with a problem, and while I won't spoil the fun with a recitation of the plot points, this book has everything a mystery-thriller needs. Plot twists, trusty sidekicks, beautiful dames, unexpected complications and a nice mix of old-school P.I. melded with high-tech gadgets, dead bodies and a race to the finish line make this very readable and highly recommended.

He honors language and ends with a graceful poignancy that has me thinking about it weeks later. Given how many books I read, one that lingers as his does is a rare and special treat.

An author is always happy to receive a positive review, and when it is as well-written as this one, it is a double pleasure. Thank you “bobwriter”. http://www.amazon.com/Blood-Money-Nathan-Everett/product-reviews/098172499X/ref=dp_top_cm_cr_acr_txt?ie=UTF8&showViewpoints=1

11 June 2011

I’ve had lots to write about—not to blog about—this week. I guess in some ways I associate the blog with what I say, not what I write. Like many blogs I read, mine is often filled with spontaneous words that come out more like a conversation; and, like this post, often don’t know where they are going until they arrive.

By comparison, I wrote a combination letter to my daughter and five-minute talk for Father’s Day. (Sorry, you can’t read it until I present it next Sunday at NUUC.) I’ve known for weeks that I’d be giving the talk and was completely at a loss as to what I would speak about. The idea came to me a few days ago. It had only a theme. Sometime Thursday, I added a point. When I walked the dogs yesterday (about 45 minutes to the coffee shop and back), I structured the whole piece in my mind. When I got home I had six points, an organizational flow, and a couple of key phrases. I started to write.

It took two hours to generate the 895 words of “Promises to my Graduating Senior.” I shared it with my wife for editing. We both cried through it. I don’t know how I’ll get through speaking it in church.

I’ve written the unspoken.

On a separate subject, I wrote the first draft of my article for Line Zero magazine, which is due by Wednesday. “Pre-Release Marketing 101” started out with a series of blog posts I wrote about launching a book. Conceptually, I had 10 things to say. But my 2,500-word article doesn’t allow for long lists like that. (I learned that last time.) I winnowed it down to just four things. Each of those four things could have been a 2,500-word article. But a lot of that will go unwritten because it is really what I would say if I were presenting the subject.

The spoken goes unwritten.

If any of this makes sense, then you are probably reading what I am thinking and not what I’ve said. But that’s a different subject.

05 June 2011

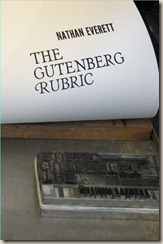

I’m pretty pleased with the cover art for The Gutenberg Rubric, as I’ve already mentioned. But I thought some people might be interested in the process we used to create it. After all, there aren’t all that many people who have access to a print shop, and I have an obligation to share the experience! So here’s a step by step.

I became pretty familiar with all the tiny bits of lead that would be used for spacing. The first picture are just spaces in various type sizes. Those are used within the line to make it come out even and to add space between words or characters. There was also a little box of brass in the point size I was using. The brass spacers are only one point thick. The lead spacers ranged from a square em down to an en, 4 em, and thin space. The second picture is the lead that goes between the lines of type. I set the title solid, but added lead between the author and the title.

This is the coolest part about setting type. I put the letters in the composing stick, setting them from right to left and adding spacers at the end of each line to make a perfect 25 pica line. There is a little nick on the front edge of each type bit, so you can feel whether you have the letters all right side up. Not so difficult with this size type (36 point Artcraft titling caps. The author’s name was set in Alternate Gothic No. 1 at 30 points.

Dan Shafer, a member of the Seattle Center for Book Arts and instructor in book arts at Cornish College for the Arts, stepped in to tie the type so it wouldn’t shift when we put it on the press. Because it was such a small job, we didn’t lock it up with furniture all around it when we put it in the tray. Dan just inked the type and we were ready to roll.

After several test pages, we were able to pull a page that was clean and hold it in position with clips until I could get a good picture for the cover. We experimented with different lighting conditions, paper stocks, and lens openings until I got one that I felt was usable.

And from that we get the final artwork for the cover. I tried various alignments and actually have pictures in which the type lines up almost perfectly horizontal on the page, but I like the dynamics of this shot the best. (It wraps around the spine and back cover as well!)

I’ve always been a big fan of photographic covers on most adult fiction, but also have had a hard rule that the photo would not include the type. Now I’m breaking that rule, but to make sure that the type is clean and clear on the cover, I did a little black enhancement in Photoshop being careful not to affect the letterpress edge of the characters.

The Gutenberg Rubric will be released in July.

27 May 2011

“It seems like this has been a long time coming, but at the same time it has happened so quickly,” Everett said. “It’s a book that came from my love of print history and a fascination with Gutenberg that started when I visited the Gutenberg Museum in Mainz, Germany in the early 90s.”

Just months before the completion of the famous Bible that bears his name, Gutenberg was sued by his financial partner for diverting funds to a secret project. When Gutenberg would not share the project, the courts awarded the entire Bible printing business to Johan Fust, leaving Gutenberg with nothing but his secret.

Modern-day rare book librarians Madeline Zayne and Keith Drucker are unlikely heroes crossing the U.S. and Europe to track down the legendary tome Gutenberg was working on. When found, it proves to be an encoded rubric that reveals the final resting place of the Library of Alexandria, hidden by its protectors 2,000 years ago. Greed, fear, biblio-terrorism, and Homeland Security stand between the lovers and the discovery of the world’s greatest collection of ancient documents.

Once inside the library, however, will Keith and Maddie survive to reveal the treasure to the world, or share the tomb of an ancient king?

A signed galley proof of the book is being offered as a prize for #ArmchairBEA this week and eBook review copies will be available early in July. Contact Nathan Everett at wayzgoose@comcast.net to request a review copy or to suggest venues for the book tour in September 2011.

23 May 2011

Book Expo America (BEA) is the number one industry event for the publishing industry in the United States. It is where publishers announce their upcoming season of books and try to get the hype built. Reviewers, readers, bookstores, distributors, and authors go to the convention at Javits Center in NYC to collect dozens of pre-release and released books (free samples), to make buying decisions, and to compete for a minute of glory on one of the platforms where readings, interviews, technology demonstrations (age of eBooks), and other hype is displayed with high hopes for the future.

I’ve been privileged to attend BEA and be a presenter there in the past. But this year, circumstances prevent my being in NYC. So I’m one of the many who will participate virtually through ArmchairBEA. Organized over the past couple of years as book bloggers and publishers cooperate together through Twitter and blogs, ArmchairBEA has become the book industry’s premier virtual event.

Today, we introduce ourselves. Here goes:

I’m Nathan, AKA Wayzgoose.

Blog address is Writer’s Cramp: http://wayzgoose.livejournal.com/

Websites: http://longtalepress.com and http://nwesignatures.com

Twitter: @wayzgoose

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/Wayzgoose (mention ArmchairBEA in friend request)

In 140 Characters: Author, Publisher, Book & eBook designer. Working in the virtual world. Living in the real world.

If you could put one book in the hands of everyone you come in contact with, what would it be and why?

Well, that’s easy, it would be my book. Why? Because I love to tell stories and it is so much better when someone is listening.

What book are you looking forward to reading the most in 2011?

Mary Doria Russell’s new offering, Doc. I’ve long appreciated Ms. Russell’s work and after hearing her speak last week, I can hardly wait for my copy to arrive!

If you could have lunch with any author, living or not, who would it be and where/what would you eat?

When it comes down to it, I’m really not that much of a Fanboy when it comes to specific authors. But I think that I’d enjoy a meal with Dorothy Sayers (Lord Peter Wimsey mysteries). I imagine that we would eat at a teashop or pub near Oxford where some of my favorites are set. Ms. Sayers helped introduce me to the concept of reading for pleasure—something that I hadn’t known in my youth.

Giveaways: Officially, tomorrow is Giveaway day, but they start today. Join ArmchairBEA and you will automatically be eligible to receive a free ePUB eBook of Steven George & The Dragon. That’s my promo this week. (Of course, there will be other giveaways from both Long Tale Press and NWE Signatures, including an ARC of my newest thriller, The Gutenberg Rubric!)

11 May 2011

One of the disadvantages of living in your own fantasy world is thinking that what you imagined is what really happened. For example, I imagined that I had posted this blog yesterday in support of Peggy McColl’s new book, but my mind played a trick on me and I found it still on my desk. I think I need to see what is under it. There may be all kinds of things I imagined I told you!

If you have a product or service you’d like to sell, a book you’ll soon release, or a passion you’d like to turn into a business, 99 Things you Wish you Knew Before Marketing on the Internet was written for you! It certainly was for me.

New York Times Bestselling Author Peggy McColl has the tried and true formula to propel your message through the virtual world and land you at your rightful place amongst the stars.

99 Things you Wish you Knew Before Marketing on the Internet makes the daunting task of marketing your product online, a straight forward step by step process so that you, too, can enjoy the same success Peggy has realized in her own life. With collaborator Judy O’Biern, President of Hasmark Service, Peggy gives you a ‘behind the curtain’ peak inside two of the brightest minds in online marketing today.

I wrote about Hasmark and partner launches a few days ago. (Lessons from the Launch-Pad—Partnering) Frankly, I wish I’d read Peggy’s book before I launched Steven George & The Dragon!

If you act now, you’ll be entered to win one of three amazing prizes. And you’ll have free access to a valuable collection of bonus gifts from top authors like Arielle Ford, Eldon Taylor, Deborah King and Caroline Sutherland.

“One of the best things you can do for yourself and your business, if you want to succeed, is to study this book!” – John Assaraf, New York Times Best-selling author of “The Answer and Having it All”

99 Things you Wish you Knew Before Marketing on the Internet was written by the best so it’s got to be good!

This is my first partner launch of a book—a subject that is close to my heart—and I managed to not get it quite right. But you can help redeem my failing memory by visiting Peggy’s site and taking a look at what she has to say. There are going to be more lessons from the launch-pad soon!

28 April 2011

(This article is inspired by a blog post by Joel Friedlander, a book designer and independent publisher in Marin Co. CA. You can read his post at Your Book Launch: Soft or Hard? I’ll be referring to Joel’s post often in the next few posts.)

I discovered a lot about book launches when I released Steven George & The Dragon on March 26. Part of what I discovered was how exhausting and in many ways stressful launching an independently published book can be. Some of the lessons I learned are worth passing on. When compared with the comments Joel makes about the differences in soft and hard launches, these thoughts might help others to get it right. For the sake of our reference, I’ll define hard launch as any book release that is tied to a specific date and appearance of the author with a book-signing and sales all targeted to that rocket the numbers of books sold on that one day.

Lesson 1: It all starts way ahead of the book. If you are doing a hard launch, one of the things you have to do is get you list of potential buyers put together. Potential buyers are: a) People in your target reading market, b) People who buy books for your target reading market, c) People who review books for your target reading market, and d) Everyone else that you know or have met or can figure out a way to get an email address for. The key element here is that you need to build a list of people you can invite to your launch and encourage to buy your book. Don’t underestimate the power of selling to friends and relatives. They all want to see you succeed. And, you’ve been attending writers’ conferences, workshops, readings, book clubs, job socials, and completely unrelated events for business or pleasure. If a person has given you a business card, they are on your list. Goal: No less than 500 names and email addresses, at least half of which must be local and in reach of your launch event. Success: I sent only 430 invitations to my launch party for Steven George & The Dragon. Nearly 70 people showed up for the launch.

Lesson 2: Inspire people to buy the book before it is released. This is really tough. Why would anyone come to your website and buy a book that isn’t released yet? Find a cause that you can couple with that will drive sales of your book. Contribute the initial sales or the a percentage of it to a favorite charity, release the book at a church or charitable event that benefits from the release, offer a pre-release discounted book price, or whatever you can do to encourage people to buy that book before it is released. This is almost impossible to do if Amazon is fulfilling your orders, but if you are handling sales from your own website, you can offer any incentive you want. Goal: 100 sales confirmed and paid before you launch. Success: In spite of offering to split the gross profits from advance sales of Steven George & The Dragon with Room to Read, an organization I have supported for many years, I sold only three copies through the website in advance. Many people told me they were waiting to buy the book at the release party. I extended the donation offer through the release party and was able to donate over $200 to Room to Read.

Lesson 3: Have a back-up marketing plan in place. What happens after the launch? I had great sales at my launch party, including many people who bought Steven George & The Dragon, For Blood or Money, and even my charity cookbook Feeding the Board! Over 70 sales that night. It was a great launch. But Amazon shows no sales since that date on any of the books in any of their versions. I’ve sold a modest number of books at a couple of other events at which I spoke, but was so focused on my one big night that now I’m scrambling to create momentum again and find myself weeks (maybe months) behind the curve.

These three lessons are heavily influencing the plans for my next launch in July. I’ll be exploring the lessons learned and the plans for the next launch over the next few posts. In the meantime, help with the title and cover of my next book by taking the 90-second survey at http://www.surveymonkey.com/s/HK2D2NP. The responses I’ve received so far are already influencing my decisions on how to launch the new book. Join in and enter to win a pre-release copy of the book now!

19 April 2011

Writers are joining the pseudo MEME started by Joe Beernink and Jason Black. I was so inspired by reading these two posts that I have to jump in and add my own story to the collection.

I have three older sisters (by 10 or more years), so when I came along our house was already full of books. I remember odd bits of storybooks, but very little specific about them. The Velveteen Rabbit was on the shelf as was some book I remember as being particularly intriguing with “Peter” in the title. But I don’t remember much more than the cover. The first book I remember poring over was the fascinating History of the New World—one of my sisters’ textbooks. There were pictures with lengthy captions, and that is what I read. I might have been 7.

But the real influence on my love was from two books. The first, a literary mystery by Celia Fremlin titled The Hours Before Dawn. It won an Edgar Award for Best Novel in 1960. It was the first book I remember reading because I chose to read it. No one told me I had to. It was way above my reading and maturity level and was a subject (sleep deprived mother afraid she is becoming psychotic) with which I had no familiarity. I remember, though, being completely caught up in the atmosphere and feeling of the story. I could imagine what it must feel like going for hours without sleep and seeing things that might or might not have been there. And then the fire. The boarder leaping from the window thinking she had stolen the baby and dying with an empty bundle of blankets in her arms. Vindication for the mother. I have not read that book in 40 years, but the imagery is still fresh in my mind. I thought that if I ever wrote a book I would want to make people feel the way that book made me feel. I was 12 years old. The book was shelved right next to Saul Bellow’s Herzog which I started and put down numerous times. The two books, however, were so closely associated in my mind that until I looked it up I thought Bellow had written The Hours Before Dawn!

The other book that was important to me is still within five feet of where I’m sitting. It is a book of poetry titled simply The Poems of Robert Browning. published first in 1896 by Thomas Y. Crowell, this is a 1924 edition with a biographical sketch by Charlotte Porter. It was my father’s—one of a dozen books of poetry that he kept. Once again, the poetry was way above my head when I first read it. I suffered through piecing the story together of “How they brought the news from Ghent to Aix.” But the romantic in my heart can still quote the opening stanza of “Cristina.”

She should never have looked at me if she meant I should not love her!

There are plenty … men, you call such, I suppose … she may discover

All her soul to, if she pleases, and yet leave much as she found them:

But I’m not so, and she knew it when she fixed me, glancing round them.

Yes, I loved the language and the poetry—the complexity of the structure that taught me that the poem was not about the rhyme. But none of that was what drew me to this volume. This book is so much more. The cover, tattered and the edged chewed by an unknown rodent is a soft brown suede/leather. The front is tooled with an ornate pastoral scene and in a banner over the top in simple gold embossed letters are the words “Robt. Browning.” That’s all. No title of the work. The title mentioned above appears on the title page inside. No, picking up this book was like picking up the secret journal—the life—of a single man who was embodied in this book.

Inside, marbled bookpaper lines the cover and flyleaf. It is so tattered now that you can see the mesh that was used to glue the sewn pages together at the spine. After two blank pages, you find an engraving of Browning with a tissue cover paper that is printed with the words “Robert Browning at 77, 1889 (His last photograph).” The paper on which the body of the book is printed is almost as thin as Bible paper, but coarser in texture. The typesetting of the foreword and biographical sketch is cramped and occasionally the letters are broken. The poetry, however, has generous margins preserving the poet’s line length and phrasing except in the very wordy lines like those of “Cristina.”

I fell in love with the book, not the wonderful words within it. It was joined on my shelf by other works from my father’s library and not a few that I collected myself. Burns, Tennyson, Milton, even Elbert Hubbard! All in soft leather or deer hide covers with intricate tooling. All dating from about 1880 to 1930. All handset with lead type and printed a page at a time on small presses.

I didn’t really start reading for pleasure until I read The Hobbit in 1967. But my love of books was already firmly ingrained. Books contained the essence of the author, wrapped in elegance and art. Meant to be held, admired, and cooed over like a lover in your embrace.

Such am I: the secret’s mine now! She has lost me, I have gained her;

Her soul’s mine: and thus, grown perfect, I shall pass my life’s remainder.

Life will just hold out the proving both our powers, alone and blended:

And then, come next life quickly! This world’s use will have been ended.

From Jason: I loved Joe Beernink’s blog on this subject so much I’m writing this response. I think it ought to become a meme among us writer-types. So to anyone reading this, I’ll make you this deal: post your own reaction on your blog, post a comment here with a link to your blog, and I’ll do my best to drive readers your way through my own social media network. Please share. Even if you don’t have a blog, give us your formative book experiences in the comments. I’d love to hear other people’s stories of how their literary love affairs began.

And so shall I.

13 April 2011

Here’s a sneak peek at my article in Line Zero magazine coming out next week. While the most common complaints about self-published work reported by readers is editorial (poor writing, editing, proofreading), there are distinct production and design issues that make a book look amateurish. Here’s what I have to say about those:

- Flat, drawn cover art and bland cover typography. Photo art on covers sells books. Only in instances where the book is targeted to younger readers or has fantasy artwork should the cover not be photographic.

- Times or Times New Roman. Using default computer typefaces screams “Amateur!” At the same time, the typeface shouldn’t be different for the sake of being unusual. Select an appropriate, readable typeface. Popular professional typefaces include Garamond, Caslon, Baskerville, and Book Antiqua. Good san serif faces include Franklin Gothic, Helvetica, and Frutiger (not Arial or Calibri).

- Double spaces after punctuation and between paragraphs. You have entered the world of professional book typesetting, not blogs, web pages and software. The correct convention for spacing is single spaces after punctuation and first lines of paragraphs indented with no additional space between.

- Typographer’s punctuation. While most word processing and layout programs automatically convert quotation marks to “curly quotes,” it is not uncommon to see self-published works produced with typewriter quotes (") and apostrophes and double hyphens for em-dashes (—). Use the proper symbol for ellipses (…), not three periods.

- Expanded spaces in justified text. Use layout software that will maintain visually consistent spacing between words and letters rather than just spreading the space between words to get even line lengths. Good dictionary-based hyphenation is an aid to well-justified text. Also monitor widow and orphan controls to make sure that the bottom margin of text is consistent throughout the book and does not change in order to prevent single lines at top and bottom of pages.

- Rough or flimsy paper. Unless you are making a reputation for yourself in “pulp” fiction, your book should be printed on 60# white paper or better. Printing on coarse, low-grade, or flimsy paper stock will make your book look cheap and uncared for.

- Oddly sized book. While bookstore shelves are slowly filling with books in more and more sizes, the standard for trade paperbacks continues to be 6x9 inches, and for mass market paperbacks 4.25x7 inches.

You can read more about the mechanics of publishing in the new issue of Line Zero and see pictures illustrating a couple of common problems in both print and eBooks. I’ll also be speaking on this subject Thursday, April 21, at the PNWA Monthly Meeting in Bellevue. (http://www.pnwa.org)

11 April 2011

I’m not attempting to give a definitive answer to this question. It wasn’t even a debate five years ago. It’s been brought to the forefront by the rise of online book sales, print-on-demand, eBooks, and enabling technology. There are those who still cling to the absolute thesis that there is no difference. If you publish your own work you are a self-publisher no matter what you call yourself. And by that narrow definition, I have to agree. But fundamentally, I believe a difference is evolving and I’d like to contribute to the debate even if I can’t openly declare a winner.

05 April 2011

No, that’s not news from my family. That’s you as an unpublished author of a beautiful new book that you’ve just labeled “finished.” I don’t mean finished as in you just got done with NaNoWriMo; I mean finished as in you’ve edited and revised and reworked and rewritten to the point that you know you have a future best seller and all you need now is a million dollar advance. You’ve printed a copy of your book on clean white paper and lovingly and tenderly tucked it into a box marked “for submission.”

Well, writing that little gem and the afterglow that resulted when you wrote your little version of “happily ever after” was the easy part.

My new guide to independent publishing will show you exactly what to expect over the next nine months as you get ready to push that little baby out into the big wide world.

I’ll be using a few of my Journal posts in the next few months to explore some of the issues and procedures for moving your book from “finished” to “published.” I’ve just completed the process myself with Steven George & The Dragon, so both the successes and the failures are fresh in mind. I’ll even be speaking on the subject at the Pacific Northwest Writers Association (PNWA) monthly meeting on April 21 at Chinook Middle School at 7:00 p.m., then again on a panel at the summer writer’s conference.

The tentative title is “Writing was the Easy Part: A guide to becoming an Independent Publisher.” I’d love to hear what you think of it and what questions you wish someone would answer about the publishing process.

Let me know!

31 March 2011

Tomorrow starts Script Frenzy, the April version of NaNoWriMo that promotes film, stage, and graphic novel scripts. I participated last year and generated a full two-act stage adaptation of my recently released novel, Steven George & The Dragon. Now I’m ready to try my hand at a film script. Here’s the tagline:

Cyber-sleuth Dag Hamar takes to the streets when he discovers a link between stolen identities and real women abducted from the streets of Seattle.

It’s a younger look at the hero of my book For Blood or Money, when he was just getting into computer forensics. Think “Taken” with an actual human as the protagonist instead of a superspy (and a story-line). It’s packed with action that Dag is completely unequipped for. The world he knows is inside the gray box of his computer, but the world he is thrust into runs from executive board rooms to the violent depths of human trafficking and focuses on the intersection of the two.

My working title “No Escape Key,” is frankly boring. I wouldn’t see a movie with that title, so why would I expect anyone else to. I liked the fact that it implied a world where the conventions of the computer that Dag is used to no longer work. And that there was no way out of it. But it needs something that actually sounds interesting.

I’m taking suggestions. Got any?

26 March 2011

I’ve experienced it in the theatre on many occasions. You slave over the scenery, lighting, sound, action, and publicity. Three hours before opening curtain, when you are getting into makeup and costume, warming up your voice, running a hair dryer on places where the paint is still wet, you hear that the house is “small.” But it is opening night and the rip in your tights, the door that won’t open, the sudden allergic reaction to spirit gum, can’t bring you down from the excitement you feel. “Overture. Curtain. Lights. This is it: the night of nights.”

The curtain opens. The house is much bigger than you were led to believe. Your mother (or her ghost) is sitting in the front row. The energy you get back from the audience laughing, applauding, even weeping, propels you to the top of your game and before you realize it started, the final curtain comes down and you take a bow.

That was last night and the launch of Steven George & The Dragon at Jitters. The house was literally packed. As many as 65 people were buying books, sipping coffee, standing in line for my autograph, and listening enthusiastically as I read passages from the new book.

Then everyone was gone. We packed the car. Lissi vacuumed the floors and Maggie cleaned up the espresso machine. The DW and I left and realized we hadn’t eaten yet, so stopped at Red Robin for a late burger & fries. Then it was home. We’re still here, looking at the remaining unsold books, trying to reconcile the reports of credit cards and cashbox with the inventory. And asking the big question that hits after every opening; Now what?

Does selling more than our goal last night make me a famous author? Will royalties, movie contracts, and bids for my next book come rolling in? Will I finally get a decent night’s sleep tonight? Any of these would be fine.

In theatre, you face a closing curtain. You start rehearsing the next show. With publishing, you start looking for another audience. A book has to have a run of more than one night, and you need an audience that doesn’t share your last name (literally or figuratively). You need Amazon sales and Barnes & Noble. You need to see the hits on your website and plan the next reading. As the famous title says, you need to “get your act together and take it on the road.”

But for today—just today, mind you—it is okay to enjoy the euphoria and glow of that opening night.

25 March 2011

This is it! Steven George & The Dragon is now officially released!

Steven George has known since his earliest memories that he would be his village’s dragonslayer. He has had the best education the people of the village could give him. He learned from the village elder, the hunter, the shaman, and the wise woman. As a young man, he is as ready as his village can make him.

When at last he is sent to slay the fearsome beast, Steven realizes he doesn’t know what a dragon looks like, exactly where it lives, or how to slay it! But Steven’s village has fostered the talent of telling tales. Steven trades once-upon-a times with a melon farmer, a village idiot, a tinker, a woodcutter, a knight, a merchant, a thief, and a gypsy. Each remarkable story leads him a step closer to understanding the true nature of his quest and that all that looks like a dragon is not a dragon.

Lost, robbed, and in despair, Steven finally discovers that all roads lead to the dragon, but a dragon may not look like a dragon!

Steven George & The Dragon is available in paperback and non-encrypted ePUB eBook from http://stngeorge.com.

Available for NOOKbook from Barnes & Noble.

Available for Kindle eBook from Amazon.com.

Available in paperback from Amazon.com.

Available in paperback from CreateSpace.com.

Release party open house at Jitters Coffee in Redmond from 5:30-8:00 with readings at 6:00 and 7:00. Come on over!

Pass the word. Today we meet the dragon!

23 March 2011

I’ve been experimenting with eBooks for ten years now. I love the industry standard ePUB format and am committed to producing all books I publish in both that and Kindle versions. But sometimes the vision for a written work exceeds the technology that is available. Let’s face it, I miss big fat leather-bound books with letterpress type and hand illuminated illustrations.

Okay. I never actually lived in an era of that kind of book, but I have some of them and they are cool. I imagine my words on those soft textured pages, being pored over by my inner child discovering a world outside the confines of my little log cabin.

Well, no one I know can afford to produce that kind of a book. They aren’t practical. Would cost too much to buy. Shoot! We don’t even have coffee tables to put them on anymore! But…

We do have the miracle of computers, and as an artist I’m able to realize my dream in pixels instead of paper. That’s where PDF comes in. I’ve had a love/hate relationship with that file format for years. Right now, I think I can use it to the best possible effect in showing people what my inner vision of my book looks like. My intent is to produce a deluxe PDF version of the book on a CD-ROM that will play on your computer. Yes, I know that isn’t the greatest reading environment in the world, but it is a great display environment for artwork. I’ve started by producing a test book, just 16 pages total. Here’s a picture from inside.

Now doesn’t that look like something you’d like to read? Turn the pages. Smell the musty odor of old paper?

It’s going to take longer to produce an entire book if I take the care I’ve taken with this sample. So, I’ve taken the buy button off my website for that particular edition. But I do have the sample available and would love your comments on it. You can click the link at Steven George & The Dragon titled “What the Sergeant Didn’t See” in the bottom right corner of the page. This is a story that doesn’t appear in the book, so you get a bonus story as well as the cool deluxe layout. You can go straight to the PDF with this link: What the Sergeant Didn’t See.

What could be better? Free story. Beautiful book. New concept. Let me know what you think.

17 March 2011

Fortunately, I knew what I was getting into when I started this project. I’ve been working in publishing for 30 years in one aspect or another and I specialized in electronic layout, design, and production of documents. I designed and produced several magazines in the 80s, training manuals and curriculum in the 90s, and both paper and electronic books in the 00s. My designs and production won prepress, printing industry, and technical communication awards and I traveled the country converting traditional publishers to desktop technology. Yes, I have credentials when it comes to the publishing process.

But even I was surprised by the time and commitment it took to publish my own book. Sure, I’ve published other people’s books and even my own through a publishing company where there were other people to depend on for editorial and marketing services. But in becoming an independent publisher, I suddenly realized that writing was the easy part.

I can sit at my computer and generate a thousand good words at a sitting (out of 5,000). The story ideas flow so fast that I keep a file of opening lines and chapters for works I want to pick up later. I have a publishing schedule of completed works that goes for the next five years. Editing, designing, laying out, and producing those works takes months.

Take, for example, editing. Steven George & The Dragon went through several editorial passes after I had finished rewriting the book to my own satisfaction and before it was ready to lay out. In a traditional publishing house, the book would have been read by a professional editor who would compare it to other books of a similar nature currently on the shelves. She would be an expert in young adult literature and would recommend changes based on a tightly defined target market. When I wrote Steven George & The Dragon, I didn’t even realize it was a young adult novel. It was my first independent beta reader, Katy, who told me precisely where it would be shelved in a bookstore. Jason, the book doctor, reviewed the “finished” draft two years ago and made substantive suggestions, largely focusing on story arc and transitions. Michele, the copy editor, sought out typos, missing punctuation, bad or confusing sentence structure, and places where words were poorly chosen. And finally, when I thought I was ready to design the book and lay it out, I sent it out to half a dozen beta readers, including some in my target market. They gave me feedback on what was missing or confusing, additional missing punctuation, and words that were too hard or unfamiliar.

I had to manage that process myself with this book. A staff editor might have used the same processes that I did, but when I finished it would have the validation of an independent third party. I guess that means I could have said someone else was responsible and relieved myself of the onus of the final say. But it all rests on my head now.

I’ll be writing more about the production process in the future, including a May article in Line Zero magazine and a presentation at the PNWA members meeting on April 21.

But I still say, writing was the easy part!